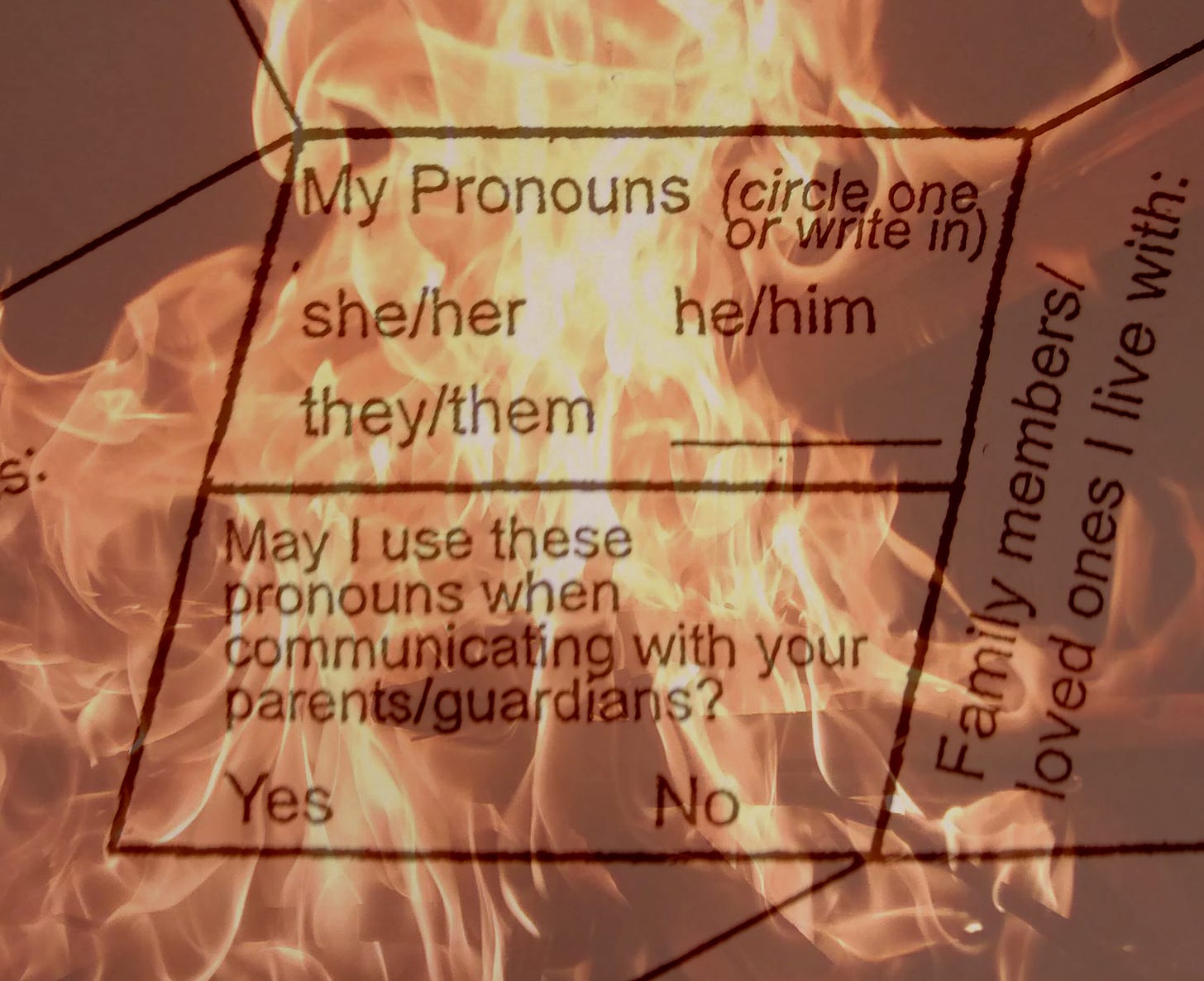

On the second day of school, I walked into a new classroom and a group of people that, for the most part, I barely knew. My teacher, both to help us get to know each other, and for her own knowledge, had a worksheet of semi-personal information for us to fill out and an icebreaker activity. As I perused the worksheet, I was unsurprised to find a section asking for my pronouns. That wasn’t what caught my attention. The part that stuck out was the second question included in the box: “May I use these pronouns when communicating with your parents/guardians?”

What?

Why would my teacher feel that she had a right to conceal, from parents, how her students preferred to be described? Are other teachers asking similar questions? And most importantly, whose interest do these questions, and their consequences, serve?

As it turns out, my teacher is not alone. In fact, Virginia Department of Education guidelines even mandate that similar obfuscatory1behaviors be codified in school policy. The Model Policies for the Treatment of Transgender Students in Virginia’s Public Schools, created by the Virginia Department of Education, in accordance with the Code of Virginia § 22.1-23.3, violate parental rights (which happens to be codified in Virginia law). These policies explicitly state that:

“There are no regulations requiring school staff to notify a parent or guardian of a student’s request to affirm their gender identity, and school staff should work with students to help them share the information with their family when they are ready to do so.”

And that:

“In the situation when parents or guardians of a minor student (under 18 years of age) do not agree with the student’s request to adopt a new name and pronouns, school divisions will need to determine whether to respect the student’s request, abide by the parent’s wishes to continue using the student’s legal name and sex assigned at birth, or develop an alternative that respects both the student and the parents. … For example, a plan may include addressing the student at school with their name and pronoun consistent with their gender identity while using the legal name and pronoun associated with the sex assigned at birth when communicating with parents or guardians.” (Emphasis added)

In short, schools are not obligated to tell parents that their child has identified as transgender and are absolutely allowed, if not encouraged, to socially transition students, whether that transition requires defying parents, or going behind their backs with deceptive communication. This, in a state that allows parents to refuse their children medical treatment for life-threatening illness is inconsistent2. Why do schools have the power to determine what’s in the best interest of students with regard to transgender student affirmation, but not in matters of other medical care? The real answer is that they don’t, and the reasons the document provides are weak.

One reason suggested by the document to answer this question is that revealing such information to parents can be risky to students with non-affirming families and that “disclosing a student’s gender identity can pose imminent safety risks, such as losing family support or housing.” However, the evidence used to support the claim is weak at best, and contradictory at worst. The initiative cited only demonstrates that LGBT youth experience higher rates of homelessness when compared to their normative peers. Even more damning, the section of the initiative that deals explicitly with LGBT youth says the following:

“Common notions of LGBTQ youth being evicted by families into homelessness after “coming out” are overly simplistic and obscure important opportunities for family-based intervention to prevent youth homelessness” (Emphasis added)

And that:

“Typically, the young person’s sexual orientation or gender identity is only one factor involved in household tensions. Most families also faced broader issues of instability, including poverty, loss, violence, addiction, mental health problems, or housing troubles. These dynamics preceded, or coincided with, the youth’s identity or coming out process.”

Far from an imminent risk of loss of housing, the document suggests that early intervention to maintain parent-child relations can be key to keeping youth out of homelessness. It also makes an explicit recognition that stable families are important to keeping youth secure at home. Encouraging youth to keep secrets is antithetical to such stability.

Closer to home is FCPS Policy 2603.23, which governs FCPS policy for transgender students. This policy is less blatant than the VDOE document, but in no way goes against the document, or improves the standing of parental rights. Instead, it uses less direct language to restate the same policies. For example, the policy says this about how schools will affirm the transgender identities of students:

“When a school is made aware of a student’s gender-expansive or transgender status, the school shall offer to convene a support team for the student or the parents. The support team shall be a multidisciplinary team that may consist of the student, parents if the student is willing, classroom teacher(s), administrator, school counselor, school psychologist, school social worker, and/or other staff members as appropriate for this collaboration.” (Emphasis added)

And it says this about how students are to be treated when parents do not affirm transgender identity:

“School staff should provide information and referral to resources to support a student in coping with a lack of support at home and seek opportunities to foster a better relationship between the student and their family.”

Nowhere are parents afforded an ability to prevent the school from socially transitioning their child, nor is there a guarantee that they will be notified of such a transition occurring if their child requests that they not be notified. In fact, a recently revealed teacher training states that no parental permission, or notification, is required for a child to request to be called a different name or to switch locker rooms to the one of their choosing. As the policies stand, the schools foster division between parents and their children, and provide them with resources that may contradict their parents as well as allowing students to keep their parents away from knowledge about, or input into, how they are treated at school4.

There is, however, a piece of Virginia state law that, if applied correctly, could confound much of this appalling policy5. Code of Virginia § 1-240.1 reads as follows:

“A parent has a fundamental right to make decisions concerning the upbringing, education, and care of the parent’s child.”

There is no provision allowing school officials to act in what they feel is the child’s “best interest,” against the wishes of parents, just clear and concise language that affirms parental control over the lives of their children. The VDOE model policies for the treatment of transgender students and, by extension, the related FCPS policies, are in clear violation of legislation that guarantees parental rights. The policies actively attempt to prevent parents from making decisions about their children and hinder the ability of parents to make informed decisions with regard to care. They must be amended, and while revision of explicitly anti-parent policies won’t remove anti-parent sentiment, it is an important step to ensuring that parents retain their fundamental rights.

I previously published this article on Valor Dictus with a few slight differences and appendations as well as footnotes. The authors note at the end of the article was summarily removed by the editors around a day after it was officially greenlit and published. As it turned out, the note was to be a false prophecy anyway (though the article in question will now be posted here). After various pressures, the editorial staff chose to further change the original, removing the image. That removal, along with the context it provides to my soon to be released work is the reason why I’m reposting it here. To see the original archive (sans authors note) click here, to see the version currently on Valor Dictus click here.

Footnotes

-

This shows up as a misspelling on the Edge spellchecker and drives me just a little bit crazy every time I see the red underline. ↩

-

Originally when I wrote this, I was under the impression that parents could make such decisions for their child if the child was under the age of 14. On a reread it seems less clear. Even so, the mention of parents being able to consider alternative treatment options suggests to me that parents should not be forced, necessarily, into providing treatment to their children that they feel is medically unnecessary, or even harmful. ↩

-

In the course of writing this I put in a FOIA request for the original version of the policy, Regulation 2603. After being linked an entirely unrelated document and then the current version of the policy, I managed to get what I was looking for, just in time to for the policy to be amended again, breaking the link that was in my document. Eventually this link will probably break too, and you’ll have to either FOIA request them yourself or trust me on the quotes (that or there’s an archive out there somewhere that I somehow missed). ↩

-

This sentence has been slightly changed from the original. ↩

-

Shoutout to Youngkin’s EO 2 for informing me of the existence of this law. ↩